Gains and Brains: Under Tension

Happy Saturday friends! Megan here. A quick editorial note: we will be returning to the Torque series soon, but my knee and back need some rehab first. All superheroes need recovery. A few people have messaged to say the injury series has been helpful, which, yay! This week though, we’re gonna channel my frustration at my joints into the newsletter, rather than whining.

I got an Instagram DM a week or so ago, pointing to a reel in which a woman purporting to be a fitness coach said she had “looked at the research,” and concluded from it that women don’t need to lift heavy.

My friend, who has spent a reasonable amount of time with me, was concerned. Have you been lying to me, Megan? Should I not be lifting heavy? Has all that nagging and cajoling been wrong and foolhardy?

“I am seeing a lot of ‘middle-aged women shouldn’t lift heavy weights’ content recently,” she said.

(That link, for the record, is ragebait around here.)

I am gonna let Carl answer the question of whether middle-aged women should lift heavy or not. (Five bucks says the phrase “time under tension” comes up.) But I want to talk about social media for a second.

One of my favourite longreads is by Ian Leslie in the Guardian. It tells the story of how we were convinced, for decades, that butter was bad for us, red meat was the enemy, and high fructose corn syrup should be in everything. To this day, my parents avoid egg yolks.

I was reflecting on that when I watched the reel. I’ve been seeing content about a backlash against protein, and “fibre having a moment.” When I step outside my carefully curated feed, I see tall thin blonde women telling me I should be doing Pilates so I don’t put my joints under pressure - and that the reformer is the same as lifting heavy. It isn’t. Pilates is great, but claims of neat equivalence between very different training stresses are where social media tends to oversimplify.

The cycle doesn’t take decades anymore. It used to be trend → backlash → research → new trend, and like in that Guardian story, it unfolded slowly. Now, confidence is being produced much, much faster than evidence. The discourse is sprinting; research is walking. And we’re all still crawling.

Whether you should lift heavy, if it’s bad for your joints, what your hormones are doing - none of those are things that can be answered in a 90 second reel by someone who doesn’t know you.

You can see how messy this gets when celebrity and medicine collide. Serena Williams - one of the greatest athletes ever - is shilling GLP-1 medications.

GLP-1s have legitimate medical uses, and for many people they’re life-changing. But when complex medical decisions show up in your feed with the endorsement of Serena and Oprah, nuance evaporates. What should be a conversation about individual health context turns into another scroll-past signal about what bodies are supposed to be doing. It’s not that the medicine is good or bad - it’s that instagram flattens the discussion into something that looks like universal advice, when it never is.

Even my desire to be a superhero sits inside this same ecosystem. The endless “look what Sydney Sweeney’s body looks like after months of training” headlines keep telling us what bodies should look like, instead of what they can do. It reinforces that we should look a certain way, if only we were doing enough.

It’s almost as if the point is to make money by getting us to stop trusting our own judgement.

The really hard part of rehabbing my knee isn’t doing the physio exercises. It’s not even being in the gym doing pathetic step-downs while my boyfriend is across the room lifting properly heavy weights. It’s that I have to manage load. I have to actually, properly, adultly rest. And I hate it.

Neither Carl, nor my physio, nor any influencer can do that part for me.

I am the only one who knows my body. Carl can give me guidance, but I’m the one deciding how many steps I can do before it hurts too much. He can write me a programme, but I’m the one figuring out how it fits into my life.

The same goes for whether you should lift heavy. I think you should - especially if you’re a woman - because being strong is cool, and having muscles that scare men is a delight. But you’re the one who lives in your body. You get to decide what you do with it, what you put in it, and what you want it to feel like.

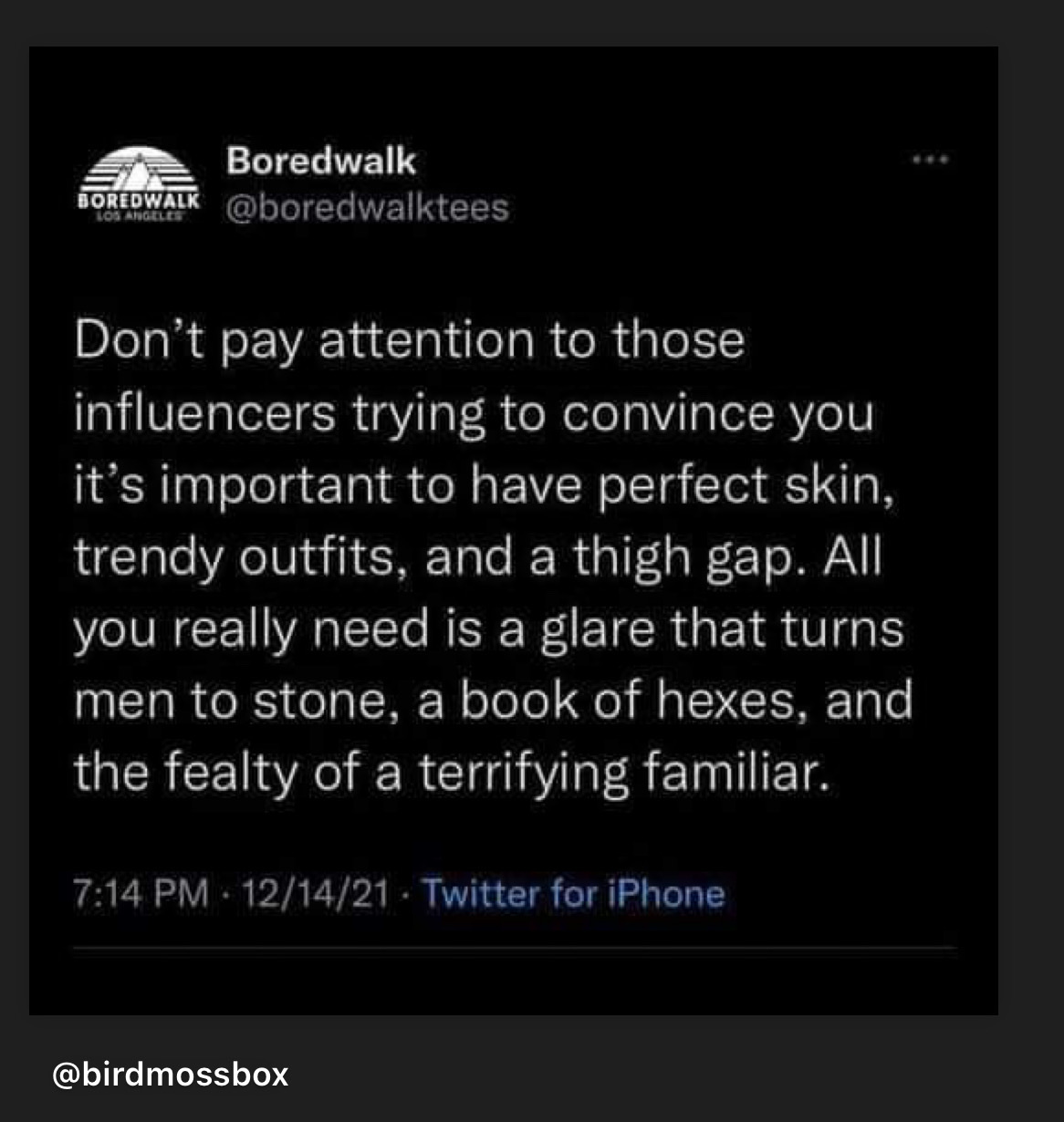

Your social feeds are designed to pull you out of that embodied decision-making. They exist to sell you things - directly through ads, by convincing you you’re not doing enough, or by making you afraid you’re going to die an early, lonely death if you miss your protein goal.

You don’t have to live like that. You can seek good advice, trust people who show their working, and experiment with what genuinely makes you feel strong and capable in your own body.

And anyone who says middle-aged women shouldn’t do anything can get in the sea.

Carl here.

Social media annoys me, mostly because you have to take a hard or controversial stance on something to stand out and get engagement. Being measured, sceptical and viewing something through an objective lens doesn't get huge interest unfortunately, but I’ll try not to spend too much time here as its already winding me up!

Let’s talk about the actual question hiding underneath the algorithmic noise. Should middle-aged women lift heavy?

Yes, but with context. With progression, with respect for tissue capacity and with far less drama than social media would like you to believe.

When people say women don’t need to lift heavy, they’re usually pointing at injury risk, joint health, or some vague idea that strength training past a certain age is unnecessary. The problem is that the research doesn’t agree.

Progressive resistance training is one of the most robustly supported interventions we have for maintaining muscle mass, strength, bone density, and physical function as we age (Liu and Latham, 2021; Westcott, 2012). This matters particularly for women, because the hormonal changes around menopause accelerate losses in both muscle and bone. Doing nothing, or only very low-load work, is not neutral. It has consequences.

Why are these two things important?

- Bone mineral density is strongly linked to mortality. Low bone density increases frailty and the risk of falls and fractures, particularly hip fractures, which are associated with significant disability and death in older adults (Johnell and Kanis, 2004; International Osteoporosis Foundation).

- Muscle loss, or sarcopenia, is also independently associated with higher mortality. Muscle is not just aesthetic tissue; it is a key metabolic and functional organ, with higher muscle mass and strength linked to better health, resilience, and longevity (Srikanthan and Karlamangla, 2014; European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People).

From a bone health perspective, the evidence is especially clear. Heavy, progressive resistance training improves or maintains bone mineral density in postmenopausal women and does so safely when properly coached and progressed. The LIFTMOR trial is a good example here.

Postmenopausal women with low bone mass trained at relatively high intensities and saw meaningful improvements in bone density and strength, with no increase in adverse events compared to controls (Watson et al., 2015). This is why organisations like the International Osteoporosis Foundation and the American College of Sports Medicine explicitly recommend resistance training as a cornerstone intervention for midlife and older women.

Heavy does not mean reckless. Heavy means heavy relative to you. This literally translates to effort, it needs to be challenging. Loads that feel challenging in the later reps, often in the five to eight rep range, sometimes higher or lower depending on the goal.

That level of mechanical tension is what tells muscle and bone that they are still required. Pilates, mobility work, and lower-load training absolutely have value, particularly for control, coordination, and confidence. But they are not mechanically equivalent to progressive loading. Different stress leads to different adaptations, and pretending otherwise is where social media tends to oversimplify.

There’s also a nervous system piece that gets missed in most reels. Strength gains are not just about muscle size. Heavier resistance training improves motor unit recruitment (makes more of your muscle useful!) and coordination, meaning you get better at using the strength you already have (Aagaard et al., 2002). That’s one reason people often report feeling more capable and stable in daily life well before any visible physical changes show up.

On injury risk, resistance training consistently comes out looking safer than people expect. When load is progressed sensibly, injury rates in weight training are lower than in many common recreational activities, including running and field sports (Keogh and Winwood, 2017).

What increases injury risk is not load itself, but sudden spikes in load. This is well described in the training–injury prevention paradox, where being underprepared is often more dangerous than being strong (Gabbett, 2016).

Which brings us back to rehab, and to Megan’s very relatable frustration. Load management is the whole game. Tissues adapt to what they are exposed to, but only if the dose is tolerable and repeated over time. No coach, physio, or influencer can feel your knee or your back. They can guide, but you still have to decide how much is too much, and when rest is the right call.

Social media makes this harder, not easier. Platforms reward certainty and confidence, not nuance. Research moves slowly and speaks in probabilities. When those two collide, confidence wins, even when it shouldn’t. That’s how we end up cycling through protein panic, fibre salvation, fear of joints, fear of lifting, and fear of getting it wrong.

I have seen both sides of an uncertain area gone viral as both were said with conviction. The problem was, the body of literature showed that the truth was somewhere in the middle, and that's not sexy! Carbs are important, carbs are bad, only lift heavy, dont lift at all ‘cos its dangerous, jump your way to dense bones, don't jump at all is not necessary and only increases injury risk!

So here’s the grounded, evidence-aligned answer. Most women benefit from lifting relatively heavy weights. They also benefit from other exercise and loads, mobility, rest, and periods of backing off when life or injury demands it. Strength is super important, and the intention is to lift heavy, but it will need to be done within the context of your life, ability and history.

If you want some practical tools that cut through the noise, start by tracking effort, not just weight. A simple one to ten scale works well. Progress one variable at a time, load or reps or sets. Leave a couple of reps in reserve most of the time, especially if you’re new or rehabbing. If pain flares and doesn’t settle within a day, that’s information, not failure. Pair heavy training with sleep and actual recovery, because adaptation doesn’t happen during the set.

You are allowed to want to be strong because it makes life easier. You are allowed to want muscle because it makes you feel powerful. You are allowed to choose barbells, Pilates, both, as long as you understand the benefits of all. What you don’t have to do is outsource your judgement to your feed.

Seek advice from people who show their working, who talk about trade-offs, and who admit when the answer is “it depends”. And remember that the part no one can do for you is the most important one: paying attention to your own body, adjusting, and living in it.

And yes. Anyone who says middle-aged women shouldn’t lift heavy can still get in the sea.