Burnout and Lifting

Happy Saturday friends! Megan here. If you are a woman, and you’ve ever told me you’re tired, chances are I’ve recommended a book called Burnout.

Burnout, by Emily Nagoski, is one of those books that fundamentally changed my life. It helped me understand that stress is my brain’s survival response. And my brain can’t tell the difference between being hunted, and someone at work saying “do you have a minute for a chat?”

Early humans might have had to flee from a marauding lion; the body would flood with cortisol, adrenaline, and other hormones to make you faster, sharper, better equipped to survive.

But here’s the thing: that response was meant to be a cycle. You’d escape the lion, then celebrate with your family, make art, or prepare a feast — something that told your body the danger was over. That’s what allowed the stress hormones to subside.

These days, our “lions” look more like traffic, work deadlines, or that one guy who keeps sliding into your DMs unwanted. And because there’s no clear end point, our bodies often stay stuck in stress mode. Unless we intentionally complete the cycle- with movement, laughter, creativity, or connection (a seven second hug!) - we end up living in a state of chronic stress.

I know this. I’ve explained it to countless people over the past few years. I even interviewed Dr Nagoski herself. Which is why it was such a surprise when I realised recently that what I’ve been feeling these past couple of months wasn’t just “winter,” but the weight of several months of chronic stress.

The penny dropped when I told Carl my joints were sore and he said, “That’s inflammation.” And the more I thought about it, the more obvious it seemed: juggling a complicated work situation, everyday life, and prep for a weightlifting competition maybe wasn’t the kindest thing I could have done for my body.

The gym has always been one of my favourite stress relievers. Throwing weights around makes me feel like I could fight the lion chasing me. And honestly, knowing I can deadlift anyone I’m in a meeting with does wonders for my patience. But maybe adding more and more physical stress on top of what my body was already carrying wasn’t the smartest plan.

By the time you read this, I’ll have been in Europe for several weeks. I’m looking forward to pasta, wine, art, sport, fashion, and all kinds of new experiences. Originally, I had planned to lift while I was away — I even asked ChatGPT to plot gyms along my itinerary.

But I’ve changed my mind. This time, I’m going to give my body what it’s been asking for. Not more weight. Not more running from lions. Just a break.

Sometimes, when I see Carl in the gym, he’ll tell me he’s really sore from the day before, and then I will see him setting up a heavy barbell. I usually frown at him and say “what would you tell a client to do?”

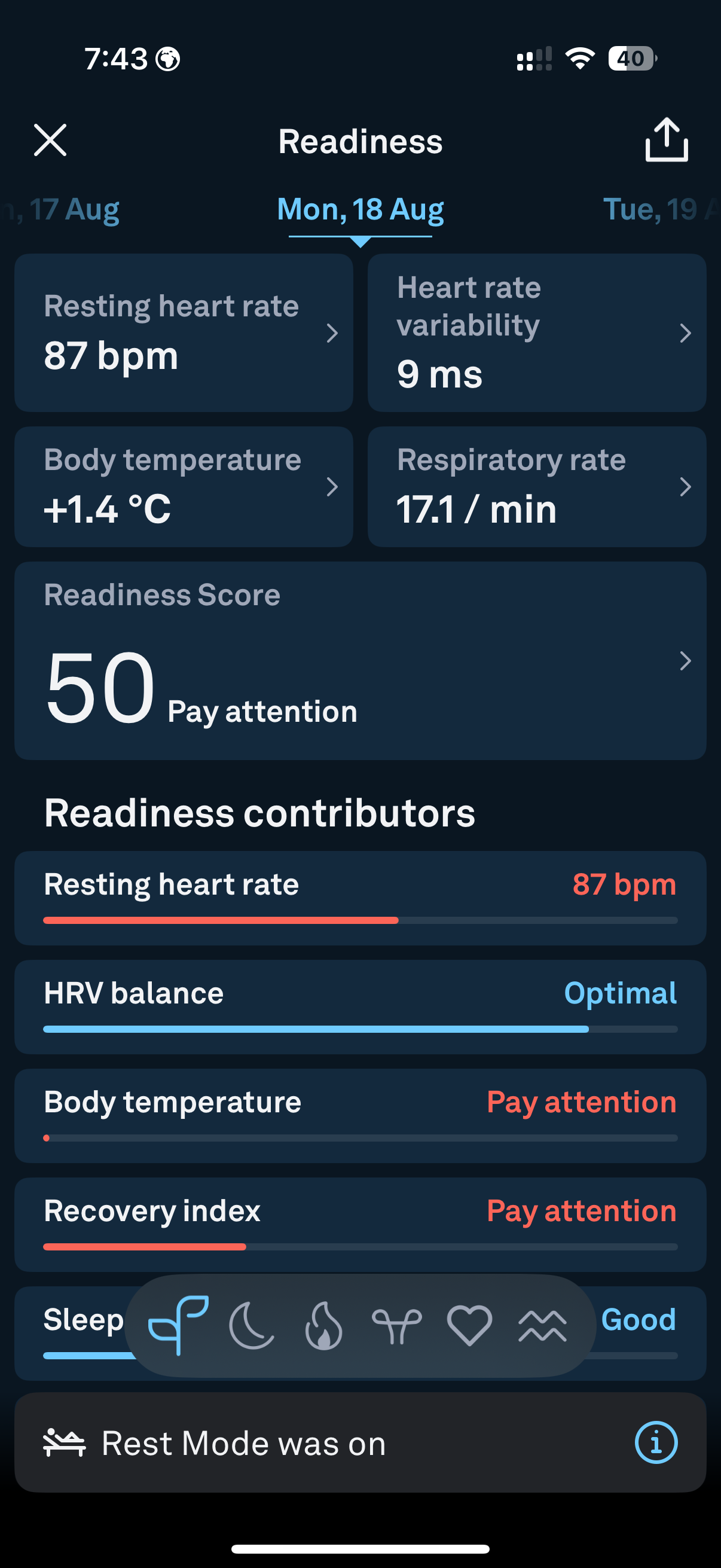

So, Carl…why were my knees so sore? And is taking a break the right thing to do? And how come when I told you my HRV was nine, you looked like I might be dying?

Carl here – this is a big and really important subject. Burnout is real, and it has many different components. In the context of training and the gym, it’s especially important to understand.

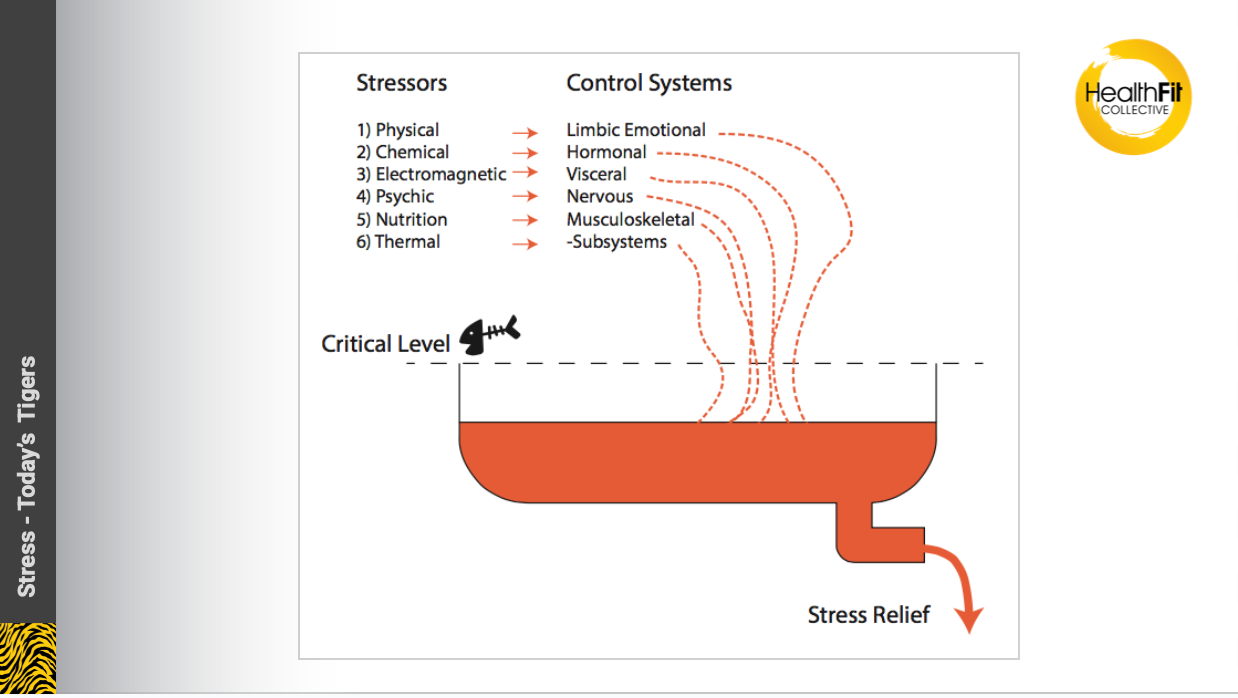

I actually run a workshop on this called Today’s Tigers. It’s all about identifying your primary stressors (your “modern-day tigers” some of which Megan mentioned above) and exploring your relationship with them. From there, we look at which factors are within your control and create practical actions around those.

It might sound like a lot, a bit like trying to eat an elephant, but the truth is, it’s far more work if you don’t address it. I also know how easy it is to just keep running on the hamster wheel, and sometimes you don't even know you're stressed or burnt out until you start coming out of it! I call this coming out of the mist. For me, this has happened when I’ve taken a break or done something to really ground myself, like a long meditation or a weekend immersed in nature.

So let’s step back and ask:

What is stress?

At its core, stress is your body’s response to a perceived challenge or threat. It activates your sympathetic nervous system (the “fight or flight” response), releasing hormones like cortisol and adrenaline. In small, short bursts, this can be beneficial, helping you lift heavier, run faster, or stay sharp for a big presentation. But when stress is ongoing without adequate recovery, what researchers refer to as ‘allostatic load’ it becomes more damaging on many systems, including the heart and brain and is linked to many serious illnesses if equilibrium can't be reached.

One thing to mention here is that psychology and perception play a role in stress. Meaning that if you perceive the stress to be a bad thing, then it will probably become a bad thing and will have a more negative impact on your health. This study explores exactly this. People who reported high levels of stress and viewed stress as a bad thing had a 43% increase in premature death and those who reported high levels of stress, but viewed it as a good thing, actually had a lower chance of premature death vs the general population.

Kelly McGonigal's TED talk summarises this beautifully.

What is burnout?

Burnout is essentially the end stage of chronic, unmanaged stress. The World Health Organization classifies it as an occupational phenomenon, marked by exhaustion, cynicism/detachment, and reduced professional efficacy. In real terms, you’ll notice it as constant fatigue, loss of motivation, brain fog, and even a sense of dread about activities you normally enjoy. It’s not just “being tired”, it’s a deep depletion across mental, emotional, and physical domains. So, Megan…does this sound familiar?

Here is a burnout questionnaire

You can see how these have a lot of crossover and perhaps are defined more by context.

So, understanding both stress and burnout. What can we do about it?

We can start with self-inquiry. This requires time, stillness and a fair amount of honesty! Ask yourself what are my tigers? I’ll cue some ideas (perhaps write down the ones that stand out to you):

Work & Career Stressors

- Unrealistic deadlines / constant workload

- Lack of control or autonomy in your role

- Job insecurity or restructuring

- Difficult boss or team dynamics

- “Always on” expectation (emails, Slack, Teams after hours)

Social & Relationship Stressors

- Conflict with a partner, family, or friends

- Caring responsibilities (kids, ageing parents)

- Loneliness or lack of social support

- Social comparison (often fuelled by social media)

Lifestyle & Environmental Stressors

- Poor sleep quality or not enough sleep

- Financial strain or uncertainty

- Overstimulation (noise, commuting, digital overload)

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Poor diet and irregular eating patterns

Internal / Psychological Stressors

- Perfectionism and high self-expectations

- Fear of failure or letting others down

- Negative self-talk

- Lack of purpose or clarity in direction

- Feeling like you’re never “caught up”

Health & Body Stressors

- Illness or chronic pain

- Hormonal imbalances

- Overtraining / under-recovering

- Injuries that limit activity

- Big life changes (pregnancy, surgery, menopause, etc.)

So when you have identified what your primary stressors are, then ask yourself, ‘what stressors are within my control now?’

Now you've answered this, ask ‘which one do I have the time and energy to address or work on now?’

Of course from here, this becomes more about behaviour change and habit creation. We will get to this at some stage in the future!

We also need to understand what fills our cup and recharges us. This can be personal, and what nourishes me, may be a stressor to you! Some ideas that come to mind are:

- Time in nature

- Social connection with a good friend or family member

- Meditation

- Sauna/hot bath

- Gardening

- Journalling

- Helping someone else (a cool study that showed that helping someone else can buffer against the harmful effects of chronic stress).

The next thing would be to ask yourself, ‘am I getting this in my life currently?’ and if not, ‘how do I get this in my life now?’.

Why is this important in the gym context?

Because exercise itself is a form of stress. When managed well, it’s a positive stress (referred to as eustress) that stimulates adaptation and growth (think: muscle growth and cardio fitness improvements). But if you’re already overloaded from life stressors, your ability to adapt to training can be impaired, leading to plateaus, injuries, or even overtraining syndrome. For me, this translates to months worth of hard work in the gym, down the gurgler, and that upsets me!

As a trainer, for the first few minutes of the session, I ask many questions about how their day/ week and life are going.

A. Because I’m generally interested.

B. To help me gauge what sort of workout to put them through, it more than often differs from my original plan!

If their life has many stressors present, I may focus on more restorative movement like mobility work, low-moderate load strength work or some accessory exercises. I may hone in on breathing within the session and cue more movement and mind awareness. If there are minimal stressors present and they are saying they are feeling good, then that's a cue to me to push harder (still following progressive overload principle) and perhaps do some heavy strength, power training or some metabolic fitness. All depending on the wants and needs, of course.

If you don't have a coach, you can ask yourself some simple questions that can help you set the intensity of your workout.

- Did I get less than 6 hours of quality sleep last night?

- Am I under-fueled and/or hydrated today?

- Am I in pain or nursing an injury?

- Am I unwell?

- Have I experienced a high level of stress or anxiety in the past 24 hours?

I would say if you are answering yes to more than 1, I would back off and do something more restorative (mobility, walk, some pattern-based movement), and if you answered no to them all, then have at it!

Some great tools can give you an idea of how your system is at this point in time. Heart rate variability can be a great tool as it is one of the best measures of how restored and physically ready your body is to perform. This research looks at the link between HRV, exercise, and work-related stress. Some smart devices can give us an HRV score and some can be presented as a body battery, giving you an indication of how much to push in your session.

So, to wrap this up: Stress is part of life, burnout doesn’t have to be, and the key is learning to dance with your modern-day tigers instead of running from them. The goal isn’t to eliminate stress, but to complete the cycle, balance training with recovery, and listen when your body whispers before it screams. Sometimes that means exercising, sometimes it means a phone call with a friend, and sometimes, yes Megan, it means pasta and wine in Europe instead of deadlifts. And as for me, setting up a heavy barbell while moaning about being sore? I know better…

Cool things we saw this week:

Sleep the night before training is one of the strongest predictors of injury!

Caffeinated coffee benefits muscle mass, but not decaf, in this recent correlation-based study. Potentially because caffeine and a compound called chlorogenic acid both activate metabolic sensors that boost glucose uptake in muscle and maintain cellular recycling that keeps muscle proteins healthy.

No whey! 30-60g of milk protein, especially whey, lowers cholesterol, triglycerides, and systolic BP in this new Meta-Analysis study.