Bright Orange Road Cones

My physio exercise this week is a step-down. Literally that. Step down from a platform that’s… maybe four inches off the ground.

And yet, when the excellent Riley said, “OK, and now step downs,” I felt muscles seize all over my body. For some reason, stepping down off a box felt like the hardest thing in the world.

Once I’d forced myself to do it twice, my brain went, “OK, what were you worried about? You’re totally capable of this.”

Carl can correct me if I’m wrong, but I’m increasingly convinced that a lot of injury recovery is reminding your body what it’s capable of.

I’m not just talking about the nervous system part - the bit where pain isn’t necessarily a sign of damage, but a sign your nervous system is trying to protect you. I understand, logically, that my knee is probably not irrevocably broken. Something felt off, and my nervous system responded by laying down bright orange road cones: proceed with caution. It’s not being dramatic. It’s trying to keep me safe.

Step-downs aren’t about correcting a lifetime of being slightly nervous on stairs. They’re an eccentric movement designed to remind my glutes that they can take some of the load off my knee. I get that. It still sucks. (There are also Bulgarians - with a hold - so yes, quite a lot of suck.) And even when you understand the why, there are still very real nerves.

I’ve been asked a few times recently how I knew what to do when I first started lifting. The short answer is: I didn’t. I had a brilliant trainer, and I am a nerd who likes to understand how things work. When I couldn’t feel deadlifts in my glutes, I asked the internet why. I tried things. Over time, the movement made sense.

I project confidence, but sometimes I’m also just re-watching a TikTok fifteen times to work out where she’s putting her feet.

I think sometimes we believe we have to understand things deeply before we’re allowed to try them. We think we need to know what every machine in the gym does before we walk in. That we need a respectable 5km time before we can call ourselves a runner. That we need to lose weight before we’re allowed to move our bodies at all.

That feels a lot like the same protective instinct. The brain trying to save us from failure by convincing us not to start.

My brain is quite good at telling me I can’t do things. This week has been hard. I tweaked my back, so now I’m sore in two places, and it’s made me cranky. It’s made me feel like I can’t do the things that make me feel good.

Lying on a yoga mat in a cobwebby, unfamiliar garage this morning, I found myself spiralling. What if these injuries never get better? What if I never deadlift 150kg?

That would suck. It’s also pretty unlikely. My knee is already much better than it was. I’ve had this back thing before, and it got better then too. So maybe my brain isn’t being a dick. Maybe it’s just being a little overenthusiastic about keeping me safe.

Instead of looking for a magic wand to fix everything, I did what I’ve always done with lifting. I got curious. I tried some things. I lay on the mat and did cobra and supine twists until my back remembered it could move without me wincing.

It’s my birthday this week, and as I get older, I’m realising that moving, staying curious, and trying things to see if they work isn’t a shortcut or a hack. It’s the practice. It’s what I’ll need to keep doing if I want to remain a “bitch who fights bears in the forest” for a few years yet.

Just like I gritted my teeth, stepped down off that tiny step, and realised it wasn’t actually that hard.

Carl here

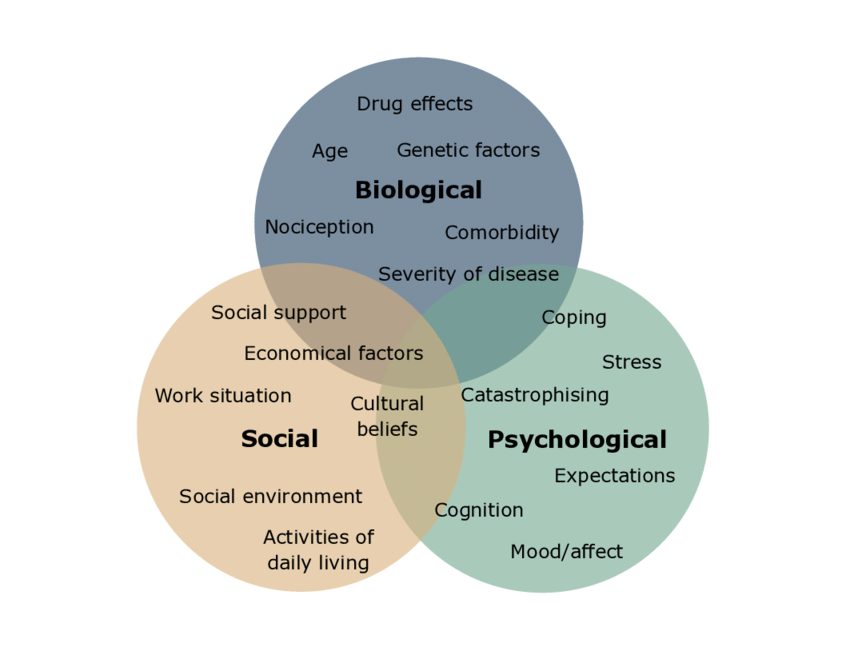

What you’re describing is something I see constantly in rehab and in the gym, and it’s one of the least talked about parts of getting back to movement. There are two main things to flesh out here (pun intended). 1. The tissue capacity and graded exposure. 2. The threat detection system in our body (biopsychosocial components previously discussed).

After injury, strength and tissue capacity usually come back faster than confidence. The body heals, but the nervous system stays cautious.

Think about it from an evolutionary perspective. If you’re walking through a forest and feel a sharp scratch on your leg, then realise you’ve been bitten by a snake, that sensation quickly becomes linked with danger. Pain, illness, and threat follow. From that point on, your nervous system doesn’t wait for confirmation. The next time a stick, leaf, or blade of grass brushes your leg, it reacts fast. Better to overreact than to miss a real threat.

After injury, the same process plays out. The nervous system remembers the context of pain and becomes quicker to warn you, even when the tissue itself is healing well. Sensations that were once neutral can suddenly feel threatening, not because something is wrong, but because your brain is trying to keep you safe based on past experience.

Pain and stiffness aren’t just signals from tissue, they’re influenced by context, uncertainty, and past experience. This is well established in pain science. Moseley and Butler’s work on pain as a protective output of the brain, not a direct measure of damage, explains this really well.

That moment where two step downs suddenly felt manageable is a textbook example of graded exposure. You didn’t argue with your brain or force confidence. You showed it evidence. This movement is safe. I can control it. Nothing bad happened. The threat level dropped.

Eccentric work like step-downs is particularly powerful in rehab because it improves load tolerance while also restoring trust. The muscles learn they can absorb force again, and the nervous system learns it doesn’t need to slam the brakes on. That combination matters more than chasing perfect technique or maximal strength early on.

The same principle applies to learning lifts, starting a new activity, or returning after time off. We don’t build belief by waiting until we understand everything. We build it by doing small, repeatable things that end better than our brain predicted. Research consistently shows that confidence follows successful exposure, not the other way around.

A simple tool I use with clients when something feels scary or fragile is this question: what’s the smallest version of this movement I could do that would still count? Not the ideal version. Not the brave version. Just the version that lets your nervous system collect a win.

Another is reframing flare ups. A spike in symptoms doesn’t mean you’re back at zero. It usually means you’ve exceeded current tolerance, not caused damage. When we respond with curiosity instead of panic, movement options open up again much faster.

Your brain isn’t trying to sabotage you. It’s trying to protect you with incomplete information. Movement, done gradually and repeatedly, is how we update that information.

And yes, sometimes that starts with stepping down off a box that looks insultingly small. In the end, consistency with graded exposure and adaptation will have you looking back on this small moment of your life with gratitude. You will prove to yourself that you have the mental grit to persevere, the wisdom to seek help and confidence to take on other challenges in your life.

Please talk with a physio and or coach if pain is persistent in your life. It can really impact on many areas of wellbeing and there is so much within your control that you may or may not know about!